Social media has had a tremendous impact on spreading knowledge and awareness on just about any topic. The way a message is conveyed and how they can go “viral” reflects the evolution of communication in more ways than focusing on just the smartphone or newest tablet alone. It is no surprise that celebrities and other influencers are taking to the internet to spread their messages. In her most recent blog post, blogger Habiba Da Silva focuses her campaign “SKIN” on highlighting both women and men of different ethnicities and cultural traditions. For Habiba, “The SKIN campaign was inspired by many things. Firstly for my passion for cultures and traditions, secondly to break up the trend of having brands with clothing dressed on only lighter skinned models.” Habiba and other bloggers and fashion designers around the world are finally bringing to the light the issue of diversity–whether it be ethnic, linguistic, or even religious.

As discussed in the previous blog post, Islam is a religion not just for Arabs or people of the Middle East. Indeed, Muslims come from all ethnicities and is growing still among inhabitants in Europe and North America. Stereotypes would tell us converts to the religion favor males, as the assumptions about Islam lead us to believe the religion oppresses women. However, evidence suggests that high rates of women are converting to Islam as well. According to the Pew Research Center, Islam is the world’s fastest growing religion and a study by Swansea University indicated that 75% of converts in the UK are women. A quick Google search will also yield blog posts and news articles from female converts to Islam discussing their decision to change religions and their journey through learning about the religion.

So–why the conversion? It is unfortunate that stereotypes about Islam would tell us that women convert to Islam because they are “brainwashed” by others, such as their Muslim husbands, friends from university, or even neighbors. If we turn this narrative upside down, we realize the stereotype does exactly what naysayers say about Islam: it removes agency and the ability to choose from the woman. When those critics of the religion claim women came to Islam because others convinced them, they are essentially claiming women are too weak-minded to make their own decisions, especially one so critical as a change in religion. Why does this happen? For starters, a reinforcement of negative stereotypes of Muslim men contributes to the problem. The idea that Muslim/Arab (often used simultaneously without regard for the difference between religion, ethnicity, and language) are tough-willed, brutish, and “wild” contributes to the notion that these men would force women to do something, such as convert to Islam. Another and related stereotype has to do with the view of Arab/Muslim women which sees them as weak, powerless and incapable of understanding reality.

Edward Said, without a doubt one of the most important scholars of the 20th century to discuss stereotypes about the peoples of the Middle East, claimed that orientalism is what created these stereotypes. The idea that the “Orient” or East was uncivilized was reason enough for the Europe (read: West) to “save” the people from themselves. This obviously resulted in colonialism of the Middle East, Sub-Saharan Africa and Central Asia. We don’t have to look far to see these stereotypes playing themselves out in the media, entertainment and in the words of world leaders. These stereotypes trickle down to everyday discussions among people and these words have impact, particularly among converts to Islam who are constantly faced with accusations of brainwashing and association with extremism.

So, again, why the conversion? Why does anyone convert to a religion? It’s a personal feeling of course, and when it comes to women, a personal choice about liberation is part of the mix. When you break through all the negative stereotypes about Islam and its treatment of women, what you find is a group of believers who truly feel the religion has opened doors for them that nothing else could and that they are reclaiming what it means to be a feminist. Theresa Corbin, an American Muslim author, wrote: “I learned that Islam is neither a culture nor a cult, nor could it be represented by one part of the world. I came to realize Islam is a world religion that teaches tolerance, justice and honor, and promotes patience, modesty and balance.” Others have claimed that Islam brought meaning to their life because it freed them from having to stay concerned with appearances, displays of wealth, and concerns for other shallow topics. Indeed, modesty is the appeal. If I don’t need to be concerned with society’s expectation to show my body, show my fashion sense, show my sexuality, then I can concern myself with more important issues, such as helping others, personal development, and devoting my life to what is good and wholesome. This is not to say that non-Muslim women cannot do this–of course they can! Rather, the appeal of Islam to female converts is that they are able to find meaning and liberation through Islam’s teaching about life and their place in the human-constructed society around them.

It is very difficult for Muslims and those concerned with their treatment to break stereotypes. Day after day, media and political pundits remind us that the religion of terrorists in the Middle East is Islam and that they are recruiting from among young people who don’t know any better–especially young women. Since a majority of the world seems to accept the notion that female converts to Islam are incapable of making their own decisions, people who watch the news and consume negative information about Islam would have no basis by which to judge whether or not conversion was forced or embraced. It is a tough situation, but the more bloggers and celebrities speak out and celebrate the diversity and exclusivity of Islam, the more the world will see the religion for what it really is.

Tag Archives: Womens Rights

Muslim Women in the Modern World

Much of how Westerners consume information about Islam comes via the most unflattering and biased outlets. The media, television programs, and films have often focused on the plight of Muslim women by selecting stories that stand out due to their instances of abuse and marginalization in the communities. It is rare, however, to find a separation or distinction being made between the women in question’s religion, society, tradition, culture, and family. It is easier for the stories to focus on lumping everything that makes a person unique together into one amorphous entity–that is, Islam. Muslim women living in or interacting with those in the West have surely felt pressure to “fight the man,” both literally and figuratively, by leaving the Hijab behind and fighting Islam as though it were in and of itself the oppressive structure in which they live. The problem with this frame of understanding is that it takes away any analysis required of the structure in which these women live.

Countries with a high population of Muslims are often called “Muslim countries” and usually refer to the Middle East, Central Asia, and a smattering of countries in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia. (It is interesting to note that countries with a predominantly Christian population are not referred to as “Christian countries” by Western media). The tendency to refer to this collection of states as “Muslim” causes the reader to assume that these states are entirely controlled by the religion. This is false. Nearly all of the countries in the Middle East have a mixed system of government whose civil code incorporates European tradition with particular applications of Islamic law. Iran, Sudan and Saudi Arabia alone claim to rule their countries entirely by Islamic law, but there are differences even within their codes and application. To note, “Throughout history and throughout the Muslim world, sharia has been shaped and reshaped, influenced by local customs, reconstructed by colonial law, and more recently by national legislatures, administrators, courts and international treaties.” Just like laws around the world, the creation and interpretation of laws for society changes over time and this reflects the negotiation and renegotiation of issues in society among members of the communities.

In regards to women and their rights, this distinction is important to make because when we assume that a country is “Islamic” we are assuming that it enacts laws and policies against women because the state has the ultimate authority and wisdom to know what is right and what is wrong. However, all of these countries are led by autocratic institutions–whether they be kings, presidents, or religious leaders–who claim they and those they employ have more knowledge or say-so into interpreting women’s roles and rights in society. Below the level of government, these issues are being negotiated among Muslim women and men, much in the same manner that men and women demanded rights and changes in their societies in Europe and North America.

Topics such as needing male chaperones, driving cars, female genital mutilation (FGM), honor killings, and arranged marriages are all topics brought up when claiming Muslim women are oppressed and without agency in their own lives. It is true that in many cases these restrictions and expectations are placed upon women and horrific violence has happened against women–this cannot be denied at all, and those who carried it out must be brought to justice. The instances of these women, however, should not be assumed and applied to all Muslim women and that all of these practices are applied across Muslim countries. In many cases, these practices that are assumed to be “Islamic” are more cultural and existed in the culture even before Islam and practiced even among non-Muslims (like FGM).

In 2013, Egypt ranked as the “worst” country for women’s rights in the Arab world out of 22 countries. Egypt, like most “Muslim” countries, prides itself on its large Muslim population and its incorporation of Shari’a law into the civil code. Two of the reasons Egypt made the top of this notorious list is due to 2 particular issues. Sexual harassment and FGM is very high in Egypt, but we cannot attribute this to Islam. In fact, most of the Egyptian women who reported harassment were wearing Hijabs or Niqabs. Sexual harassment is not condoned in Islam and FGM was actually practiced prior to Islam’s institutionalization in the Arabian peninsula. It is practiced among non-Muslims in Egypt and beyond as well, as it was a traditional practice and has been condemned by Al-Azhar’s Grand Mufti.

Egyptian women are constantly negotiating changes within their society, whether it be religious or nonreligious topics. The main thing to note is that it must be negotiated by the women themselves and not imposed and enforced from outsiders looking in. People who do not live in Egypt (or any other country heavily populated by Muslims) and judge these women as powerless do not understand the complexities of these society by merely reading news articles or jumping between Quranic verses supposedly claiming this or that. As readers and supporters of women’s rights, it is important that we be available to assist if called upon, but realize that imposing anything on anyone never works. When people demand their rights or try to change things in their culture, gradually those changes happen. When has imposing anything on anyone ever worked out–long term?

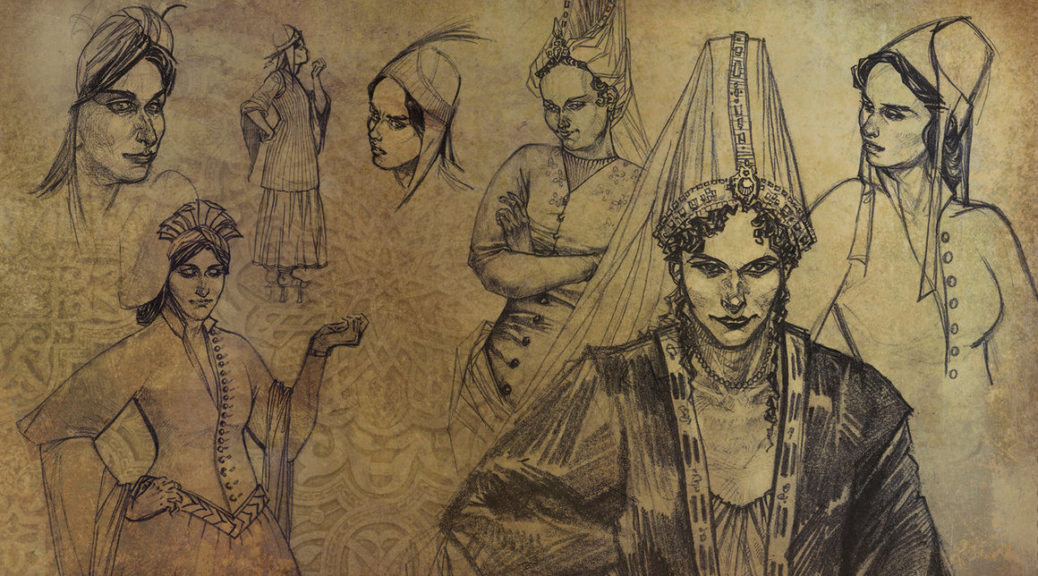

An Empire for Women: Muslim Women Under Ottoman Rule

As we continue the discussion regarding women and Islam, it would be wise to look at Muslim women in time periods beyond that of the life of the Prophet. Throughout history there have been several dynasties and kingdoms that have come and gone as civilizations do, but the Ottoman Empire sticks out as one of the largest and longest-lasting empires of all time. Indeed, the Ottoman Empire stretched from north-western Africa (modern day Algeria) all the way to the Red Sea, up into the Levant and Mesopotamia and to the top of the Balkan peninsula. The areas controlled by the Ottoman Sultans would eventually come to shape the layout of the modern Middle East as we know it today following the end of World War I. Within this large swath of land, the Ottomans ruled over various types of religious believers and ethnicities. The rules that governed the interactions among and between individuals were dictated by their religious communities and respected by the Ottoman’s laws (which were most informed by Islamic law). When we take a closer look at women living under Ottoman law at this time, what we see is a very different picture than that of women in other parts of Europe.

As with all societies, the role of men and women are constantly being negotiated and renegotiated. This was no different during Ottoman times. There is an increasing amount of research written about women in the Ottoman Empire, particularly their role in society, and how that view has been shaped primarily by Western travelers influenced by orientalism. Interestingly, however, that some Westerners have viewed women in the Ottoman times as fairly free. “This is further confirmed in the early 18th century letters of Lady Mary Wortley-Montague, in which she exclaims that nowhere else are women as free as they are in the Ottoman Empire.”

Research on Muslim women in the Ottoman Empire have revealed much. What we see are two levels of society, both defined in their own right by the power of the women in her particular sphere of influence.“Leslie Pearce argues…that women were allowed access to the public world in such instances as attending mosques for purposes of religious teachings, and that some religious leaders did approve of this type of female public appearance.” And as with most societies, Muslim women’s activities and roles varied between the upper and lower classes. For upper-class women, a sense of segregation unfortunately resulted in the Western misinterpretation of the term “harem,” which comes from the Arabic world “haram,” or forbidden. While the stereotype sees these women as powerless sexual objects, in reality, they held much influence over the wealthier men, such as the Sultan and his associates. Research even suggests that these women were the driving forces behind the development of charitable organizations and political decisions. This influence was enshrined in the position of the valide sultan (the “mother of the sultan”). Probably one of the most famous of the valide sultans was Hafsa Sultan, the mother of Suleiman the Magnificent. There are reports as well that lower-class women also developed their own charitable organizations (or, “awqaf” in Arabic). These women were able to use their personal influence via ties to wealthier subjects in society (read: men) to make their personal initiatives come to life. For lower-class women in Ottoman society, there was a sense of mobility and autonomy in public that was very different than that of more wealthy women. Many women were landholders, tax farmers, and other professions. Depending on the location that they lived within the empire, they may have been craftswomen or involved in textiles as well.

As mentioned above, Ottoman law takes into account Islamic law. In the case of inheritance, women were able to inherit land and other property. This is generally permitted in Islamic jurisprudence. In attempts to degrade the religion, critics often point to the fact that women usually only get half as much inheritance as men, but then again, there are no provisions for women to use their inheritance to support a family. Women can use it as they see fit. While arranged marriages were common practice at this time in the Ottoman Empire, women had the right to refuse a proposal. Divorce was also common and accepted and, interestingly as one scholar notes, “For non-Muslim Ottoman women whose traditions did not normally permit divorce, conversion to Islam was a common way to be liberated from an unwanted spouse.”

This last piece is very telling. How can we compare Muslim women in the Ottoman Empire to other women at this time period? In the United States up until the twentieth century, women could not easily own property unless they were unmarried. “When women married, as the vast majority did, they still had legal rights but no longer had autonomy. Instead, they found themselves in positions of almost total dependency on their husbands which the law called coverture.” This law essentially put all legal dealings for property into the hands of the man in the relationship, which was also the practice in several European countries at this time. Divorce and women working outside the home was also less common than in the Ottoman Empire at this time in Europe and the United States for reasons relating to social and religious interpretations of a woman’s place in society.

It is interesting to note the juxtaposition between Ottoman society and Western societies. While the Ottoman Empire eventually fell and gave rise to various Middle Eastern countries as we know them today, their interpretations of Islamic law varies and depends on the local context for interpretations of what it means to be a Muslim woman at that time. For Ottomans, it was women’s personal right to have access to their rightly-owned property, ability to refuse marriage if they wanted, and also to own work various crafts. This is of course different than what the more wealthy women experienced, and different still than women around the world at that time. The key is that we are able to identify examples throughout history where women were empowered due to real implementation of religious laws during the negotiations that were taking place in society at that time.

Marriage, Divorce, and Women’s Rights in Islam

As we continue our discussion of women’s rights in Islam, it is important for us to pay attention to context and history in order to understand the way women’s rights were understood during the time of the Prophet. By doing this, the role of women in the religion will make more sense in modern times. Generally, this is how religious scholars and academics study religion because, while the information and practice should be applied in any time period, the context in which the different practices and principles came about developed out of a need for the community of believers at the time. If the principle is taken out of context and applied in modern times without concern for its original application, the soul and true intention is lost. Sometimes we can see this in predominantly Muslim societies of the Middle East and South Central and Eastern Asia wherein women’s rights are sometimes sidelined or the religious interpretation is out of the sync with Quranic principles. Unfortunately, this perpetuates the stereotype that women are treated as second-class citizens in Islam. In order to address this problem and create important distinctions, comparing and contrasting using the original sources such as the Quran will allow readers to understand women’s rights as they were initially intended within the religion. The best way to begin this discussion is by comparing particular topics regarding women within pre-Islamic Arabian society as well as after Islam was revealed to the Prophet. For this blog post, we will explore the topics of marriage and divorce and women’s rights and responsibilities.

Before Islam was revealed to the Prophet and his community, a women’s position in the society of the Arabian peninsula was much different. Due to the tribal basis of Arabian society at this time as well as the traditional patrilineal custom of inheritance, men’s rights and desires almost always trumped those of women. Infanticide was common for female babies and in general, women were considered a burden on the family. The pride of the family and weight of responsibility lay with the males. This led to men marrying as many women as they chose, a lack of inheritance for women, and no choice for women whether or not to marry or divorce. Women’s status in pre-Islamic society is often described as harsh and lacking in very basic rights unless the woman was of high-status and from a well-respected family within the tribe. Women were usually referred to as a type of property and an item with which to use in trade and financial transactions. Indeed, a woman’s worth was seemingly not acknowledged, particularly in relation to a man’s value.

When the Quran was revealed to the Prophet and he recited the verses to his community, it became clear that Islam had a particular focus on improving the status of women and that this issue was something of concern for the Prophet. “In Islamic marriage, a legal contract is the basis of the union, with the rights and duties plainly laid out and mutually agreed upon by both parties.” There are many sayings and stories about the Prophet concerning women’s rights and attitudes toward women in general. His relationship with his first wife Khadijah was seen as a model for the relationship between husbands and wives. As the Quran was revealed, several verses discussed women’s rights and their choices when it came to marriage. For example, in Surat Al-Rum 21, God makes it explicit that He created humanity as man and woman and they were intended to be together and provide tranquility and affection. In Surat Al-Nisaa 1, we find: “O mankind, fear your Lord, who created you from one soul and created from it its mate and dispersed from both of them many men and women. And fear Allah, through whom you ask one another, and the wombs. Indeed Allah is ever, over you, an Observer.” In essence, admitting that men and women were created from one was radical–especially to even compare women with men, the previously exalted figure of seventh-century society. There are other verses of the Quran reiterating this idea about the special relationship between men and women in marriage which reflects the importance of marriage in Islam. These verses and others mention how men and women should respect each other in marriage, no doubt reflecting the idea that stability in the marriage relationship leads to the foundation of strong societies.

In those instances, where marriage does not work out, women do have options. There are various verses in the Quran dealing with divorce. They deal with topics such as parting on good terms, appointing a mediator, allowing for remarriage, providing support to divorced women, and allowing for reconciliation if they change their minds on divorce after the fact. These verses explicitly lay out women’s rights and responsibilities when she requests a divorce and the assistance she receives when this procedure takes place. In pre-Islamic societies, such a notion of supporting a woman after divorce occurs was unheard of. Indeed, divorced and widowed women were unsupported and considered a societal burden. By creating a basis by which women could obtain a divorce and be supported afterwards, the society begins to institute the normalization of women requesting the same rights that men ask for and that allow women to maintain a normal role in society instead of divorce leading to her shame in society.

As discussed, the rights of women concerning marriage and divorce are fairly explicit and further guidance can be taken from the Hadith of the Prophet himself. Much of the stereotypes about women’s rights in Islam often come from news clippings and scattered media coverage of sensationalist and unfortunately occurrences happening in the Muslim world. As Frederick Matthewson Denny suggests,

“As was suggested above, the original teachings of Islam, as contained in the Quranic revelation, may be seen to be quite liberating to women, whereas the subsequent history of the Umma saw the triumph of absolute male domination, not only of the institutions of Islamic civilization but also of the sources principles, and procedures of its discourse.”

The institutions and practice of the religion that has developed in Muslim-majority countries and societies may not reflect the aforementioned understanding of marriage and divorce when it comes to men and women, but this debate and discussion must be had by Muslims themselves since.

Muslim Women’s Rights and Western Intervention

Around 1,420 years ago a man in his twenties named Muhammad lived in Mecca located in the Arabian Peninsula–which is now considered part of Saudi Arabia–was known among his tribe as being honest and genuine. This excellent reputation afforded him many opportunities to take handle business for other people who were unable to travel for trade. One of the wealthiest business owners in Mecca was a woman named Khadijah. She had heard that Muhammad was trustworthy and believed that he could take her merchandise to Syria for trade. Muhammad was successful in his trade mission for Khadijah, and over time she saw him as a respectful man who could make a good husband. Khadijah proposed marriage through her friend Nufaysah, and when they did marry, their relationship was full of love and respect. Khadijah supported Muhammad when he began receiving revelations, and in fact was among the first believers in Islam. This relationship has had a great impact on how women in Islam have shaped their interaction with the religion and its practice. Unfortunately, stories of this relationship are not well-known among non-Muslims. In fact, women’s rights and efforts to improve them are not very well known out of the Middle East.

The various efforts being made today on the part of Western countries and international organizations sometimes feels tone deaf to Muslim communities both within and outside of the Muslim-majority countries (aka. Muslim world). This is primarily for two reasons. First, Muslims know that women’s rights are held in high regard in Islam, as evidenced by Quranic principles and various parts of the Hadith (or, the sayings and actions of the Prophet Muhammad). Second, there is a feeling among Muslims that when Westerners attempt to discuss topics such as women’s rights, they are imposing their own understanding of what that should look like in a society which, in some cases, may not even be completely practiced in Western countries. This complex topic often brings out the Orientalist stereotypes most commonly discussed about the treatment of women in Islam which has been informed by centuries of tense relations between the Middle East and the West.

The discussion of the role of women in Islam has been a topic of conversation in the West since the first trade merchants of the region made their way into Muslim lands. The way these merchants wrote about their interactions with women–or a lack thereof–reflects a larger perception about life in Islamic cities. This has affected the very same stereotypes many people still hold today. We can see these stereotypes played out most recently in the discussion of the French banning of the Burkini. The general discussion around this topic is similar to that of the Hijab. On one hand, the media discusses whether or not the wearing of a Burkini has been forced by men or whether it’s very appearance in public implies extremism. On the other hand, Western feminists find themselves in conversation with Muslim women about whether or not modern perceptions of feminism even permits women to choose the Burkini. Women’s rights in general, regardless of the society and religion in which they are discussed, are incredibly sensitive.

One way of understanding this is by framing our perception of women’s rights in terms of a woman’s body and society. The morality of a society is played out over the role of women; the ways in which women choose to act is often a topic of conversation in societies because her actions are very much tied to perceptions about society’s morality and whether or not the society as a whole is in decline. This is one of the reasons that Western countries discuss this topic at length when it comes to Muslim women. It is part of a perception that Western societies are superior or that their ways of developing women’s rights are more modern.

The main issue here is that these conversations are already happening inside of Muslim countries and they have been for many years. There are countless NGOs and initiatives in Muslim countries dedicated to promoting women’s rights and helping women to overcome challenges that they face in their societies. Muslim-majority countries indeed have many issues, ranging from unemployment to access to quality health care. These issues–just like women’s issues–are part of larger conversations taking place in society. The fact that Western feminists are not aware of these initiatives is not surprising, since there is very little awareness of social issues that Muslims face daily. It can be frustrating for Muslims to hear Westerners discuss human rights issues in relation to Islam because they often misunderstand or misinterpret the meanings of a variety of Quranic verses or other religious literature. By taking verses out of context, the Western critic finds ways to demean the religion and its believer. Blaming religion for a society’s problems is a common tactic in secular societies. However, it is not a new or even religious phenomenon to regulate women’s dress–this has been happening a long time.

Many books and articles have been written about women’s rights in Islam–from the point of view of Muslims and from outsiders’ perspectives. The fascination with symbols of women’s oppression in Muslim countries such as the Hijab really only creates more of a division between Muslims and Westerners since Muslims believe that those living in Europe and the U.S. take these symbols out of context and make no effort to understand. Much of this has to do with the perception that the Middle East is a monolith, having no distinction between individuals (despite the fact that the region is religiously, ethnically, and linguistically diverse). By grouping all differences into a single classification, Westerners can lose the often important pieces of understanding the Middle East. Conversations about women’s rights must include the opinions of Muslim women who are already involved in such efforts in their societies. Without their valuable opinions, more constructive collaboration cannot occur.

Sources:

Lings, Martin. Muhammad: His Life Based on the Earliest Sources. New York: Inner Traditions International, 1983.

Rubin, Alissa. “From Bikinis to Burkinis, Regulating What Women Wear.” The New York Times. N.p., 27 Aug. 2016.

Ibid