As we continue the discussion regarding women and Islam, it would be wise to look at Muslim women in time periods beyond that of the life of the Prophet. Throughout history there have been several dynasties and kingdoms that have come and gone as civilizations do, but the Ottoman Empire sticks out as one of the largest and longest-lasting empires of all time. Indeed, the Ottoman Empire stretched from north-western Africa (modern day Algeria) all the way to the Red Sea, up into the Levant and Mesopotamia and to the top of the Balkan peninsula. The areas controlled by the Ottoman Sultans would eventually come to shape the layout of the modern Middle East as we know it today following the end of World War I. Within this large swath of land, the Ottomans ruled over various types of religious believers and ethnicities. The rules that governed the interactions among and between individuals were dictated by their religious communities and respected by the Ottoman’s laws (which were most informed by Islamic law). When we take a closer look at women living under Ottoman law at this time, what we see is a very different picture than that of women in other parts of Europe.

As with all societies, the role of men and women are constantly being negotiated and renegotiated. This was no different during Ottoman times. There is an increasing amount of research written about women in the Ottoman Empire, particularly their role in society, and how that view has been shaped primarily by Western travelers influenced by orientalism. Interestingly, however, that some Westerners have viewed women in the Ottoman times as fairly free. “This is further confirmed in the early 18th century letters of Lady Mary Wortley-Montague, in which she exclaims that nowhere else are women as free as they are in the Ottoman Empire.”

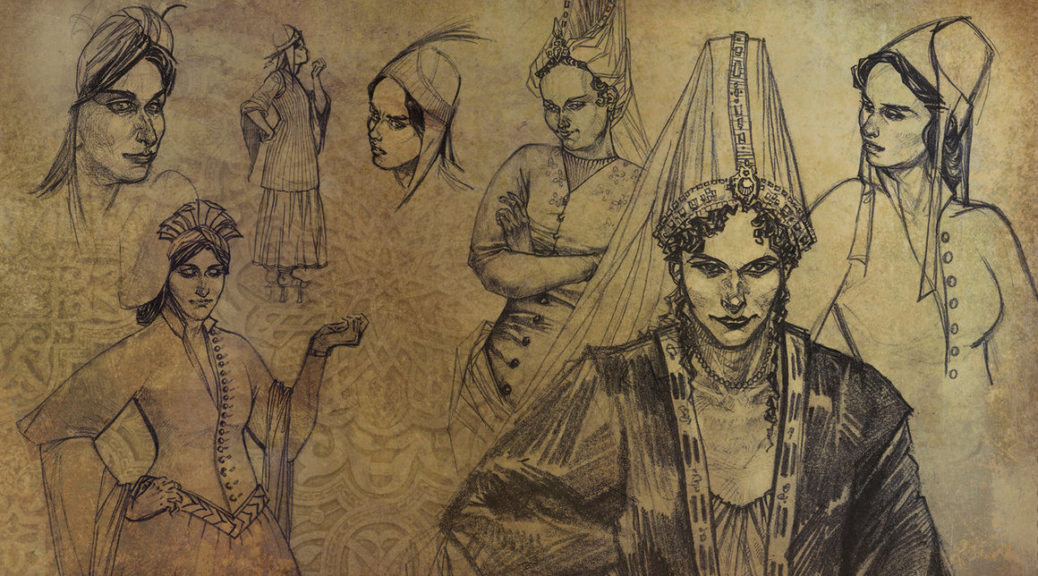

Research on Muslim women in the Ottoman Empire have revealed much. What we see are two levels of society, both defined in their own right by the power of the women in her particular sphere of influence.“Leslie Pearce argues…that women were allowed access to the public world in such instances as attending mosques for purposes of religious teachings, and that some religious leaders did approve of this type of female public appearance.” And as with most societies, Muslim women’s activities and roles varied between the upper and lower classes. For upper-class women, a sense of segregation unfortunately resulted in the Western misinterpretation of the term “harem,” which comes from the Arabic world “haram,” or forbidden. While the stereotype sees these women as powerless sexual objects, in reality, they held much influence over the wealthier men, such as the Sultan and his associates. Research even suggests that these women were the driving forces behind the development of charitable organizations and political decisions. This influence was enshrined in the position of the valide sultan (the “mother of the sultan”). Probably one of the most famous of the valide sultans was Hafsa Sultan, the mother of Suleiman the Magnificent. There are reports as well that lower-class women also developed their own charitable organizations (or, “awqaf” in Arabic). These women were able to use their personal influence via ties to wealthier subjects in society (read: men) to make their personal initiatives come to life. For lower-class women in Ottoman society, there was a sense of mobility and autonomy in public that was very different than that of more wealthy women. Many women were landholders, tax farmers, and other professions. Depending on the location that they lived within the empire, they may have been craftswomen or involved in textiles as well.

As mentioned above, Ottoman law takes into account Islamic law. In the case of inheritance, women were able to inherit land and other property. This is generally permitted in Islamic jurisprudence. In attempts to degrade the religion, critics often point to the fact that women usually only get half as much inheritance as men, but then again, there are no provisions for women to use their inheritance to support a family. Women can use it as they see fit. While arranged marriages were common practice at this time in the Ottoman Empire, women had the right to refuse a proposal. Divorce was also common and accepted and, interestingly as one scholar notes, “For non-Muslim Ottoman women whose traditions did not normally permit divorce, conversion to Islam was a common way to be liberated from an unwanted spouse.”

This last piece is very telling. How can we compare Muslim women in the Ottoman Empire to other women at this time period? In the United States up until the twentieth century, women could not easily own property unless they were unmarried. “When women married, as the vast majority did, they still had legal rights but no longer had autonomy. Instead, they found themselves in positions of almost total dependency on their husbands which the law called coverture.” This law essentially put all legal dealings for property into the hands of the man in the relationship, which was also the practice in several European countries at this time. Divorce and women working outside the home was also less common than in the Ottoman Empire at this time in Europe and the United States for reasons relating to social and religious interpretations of a woman’s place in society.

It is interesting to note the juxtaposition between Ottoman society and Western societies. While the Ottoman Empire eventually fell and gave rise to various Middle Eastern countries as we know them today, their interpretations of Islamic law varies and depends on the local context for interpretations of what it means to be a Muslim woman at that time. For Ottomans, it was women’s personal right to have access to their rightly-owned property, ability to refuse marriage if they wanted, and also to own work various crafts. This is of course different than what the more wealthy women experienced, and different still than women around the world at that time. The key is that we are able to identify examples throughout history where women were empowered due to real implementation of religious laws during the negotiations that were taking place in society at that time.

Tag Archives: Muslimah

Muslim Women’s Rights and Western Intervention

Around 1,420 years ago a man in his twenties named Muhammad lived in Mecca located in the Arabian Peninsula–which is now considered part of Saudi Arabia–was known among his tribe as being honest and genuine. This excellent reputation afforded him many opportunities to take handle business for other people who were unable to travel for trade. One of the wealthiest business owners in Mecca was a woman named Khadijah. She had heard that Muhammad was trustworthy and believed that he could take her merchandise to Syria for trade. Muhammad was successful in his trade mission for Khadijah, and over time she saw him as a respectful man who could make a good husband. Khadijah proposed marriage through her friend Nufaysah, and when they did marry, their relationship was full of love and respect. Khadijah supported Muhammad when he began receiving revelations, and in fact was among the first believers in Islam. This relationship has had a great impact on how women in Islam have shaped their interaction with the religion and its practice. Unfortunately, stories of this relationship are not well-known among non-Muslims. In fact, women’s rights and efforts to improve them are not very well known out of the Middle East.

The various efforts being made today on the part of Western countries and international organizations sometimes feels tone deaf to Muslim communities both within and outside of the Muslim-majority countries (aka. Muslim world). This is primarily for two reasons. First, Muslims know that women’s rights are held in high regard in Islam, as evidenced by Quranic principles and various parts of the Hadith (or, the sayings and actions of the Prophet Muhammad). Second, there is a feeling among Muslims that when Westerners attempt to discuss topics such as women’s rights, they are imposing their own understanding of what that should look like in a society which, in some cases, may not even be completely practiced in Western countries. This complex topic often brings out the Orientalist stereotypes most commonly discussed about the treatment of women in Islam which has been informed by centuries of tense relations between the Middle East and the West.

The discussion of the role of women in Islam has been a topic of conversation in the West since the first trade merchants of the region made their way into Muslim lands. The way these merchants wrote about their interactions with women–or a lack thereof–reflects a larger perception about life in Islamic cities. This has affected the very same stereotypes many people still hold today. We can see these stereotypes played out most recently in the discussion of the French banning of the Burkini. The general discussion around this topic is similar to that of the Hijab. On one hand, the media discusses whether or not the wearing of a Burkini has been forced by men or whether it’s very appearance in public implies extremism. On the other hand, Western feminists find themselves in conversation with Muslim women about whether or not modern perceptions of feminism even permits women to choose the Burkini. Women’s rights in general, regardless of the society and religion in which they are discussed, are incredibly sensitive.

One way of understanding this is by framing our perception of women’s rights in terms of a woman’s body and society. The morality of a society is played out over the role of women; the ways in which women choose to act is often a topic of conversation in societies because her actions are very much tied to perceptions about society’s morality and whether or not the society as a whole is in decline. This is one of the reasons that Western countries discuss this topic at length when it comes to Muslim women. It is part of a perception that Western societies are superior or that their ways of developing women’s rights are more modern.

The main issue here is that these conversations are already happening inside of Muslim countries and they have been for many years. There are countless NGOs and initiatives in Muslim countries dedicated to promoting women’s rights and helping women to overcome challenges that they face in their societies. Muslim-majority countries indeed have many issues, ranging from unemployment to access to quality health care. These issues–just like women’s issues–are part of larger conversations taking place in society. The fact that Western feminists are not aware of these initiatives is not surprising, since there is very little awareness of social issues that Muslims face daily. It can be frustrating for Muslims to hear Westerners discuss human rights issues in relation to Islam because they often misunderstand or misinterpret the meanings of a variety of Quranic verses or other religious literature. By taking verses out of context, the Western critic finds ways to demean the religion and its believer. Blaming religion for a society’s problems is a common tactic in secular societies. However, it is not a new or even religious phenomenon to regulate women’s dress–this has been happening a long time.

Many books and articles have been written about women’s rights in Islam–from the point of view of Muslims and from outsiders’ perspectives. The fascination with symbols of women’s oppression in Muslim countries such as the Hijab really only creates more of a division between Muslims and Westerners since Muslims believe that those living in Europe and the U.S. take these symbols out of context and make no effort to understand. Much of this has to do with the perception that the Middle East is a monolith, having no distinction between individuals (despite the fact that the region is religiously, ethnically, and linguistically diverse). By grouping all differences into a single classification, Westerners can lose the often important pieces of understanding the Middle East. Conversations about women’s rights must include the opinions of Muslim women who are already involved in such efforts in their societies. Without their valuable opinions, more constructive collaboration cannot occur.

Sources:

Lings, Martin. Muhammad: His Life Based on the Earliest Sources. New York: Inner Traditions International, 1983.

Rubin, Alissa. “From Bikinis to Burkinis, Regulating What Women Wear.” The New York Times. N.p., 27 Aug. 2016.

Ibid